The Killer Whale Who Changed the World

- ISBN: 9781771641937

- Tags: Literary Non-Fiction, Mark Leiren-Young, Nature & Environment, Science,

- Dimensions: 6 x 9

- Published On: 9/17/2016

- 208 Pages

- ISBN: 9781771643511

- Tags: Literary Non-Fiction, Mark Leiren-Young, Nature & Environment, Science,

- Dimensions: 9 x 6

- Published On: 8/26/2017

- 208 Pages

"Outstanding and inspirational. Similar to the award-winning Blackfish, this book could be a game changer."

—Marc Bekoff, author of Rewilding Our Hearts

The fascinating and heartbreaking account of the first publicly exhibited captive killer whale—a story that forever changed the way we see orcas and sparked the movement to save them.

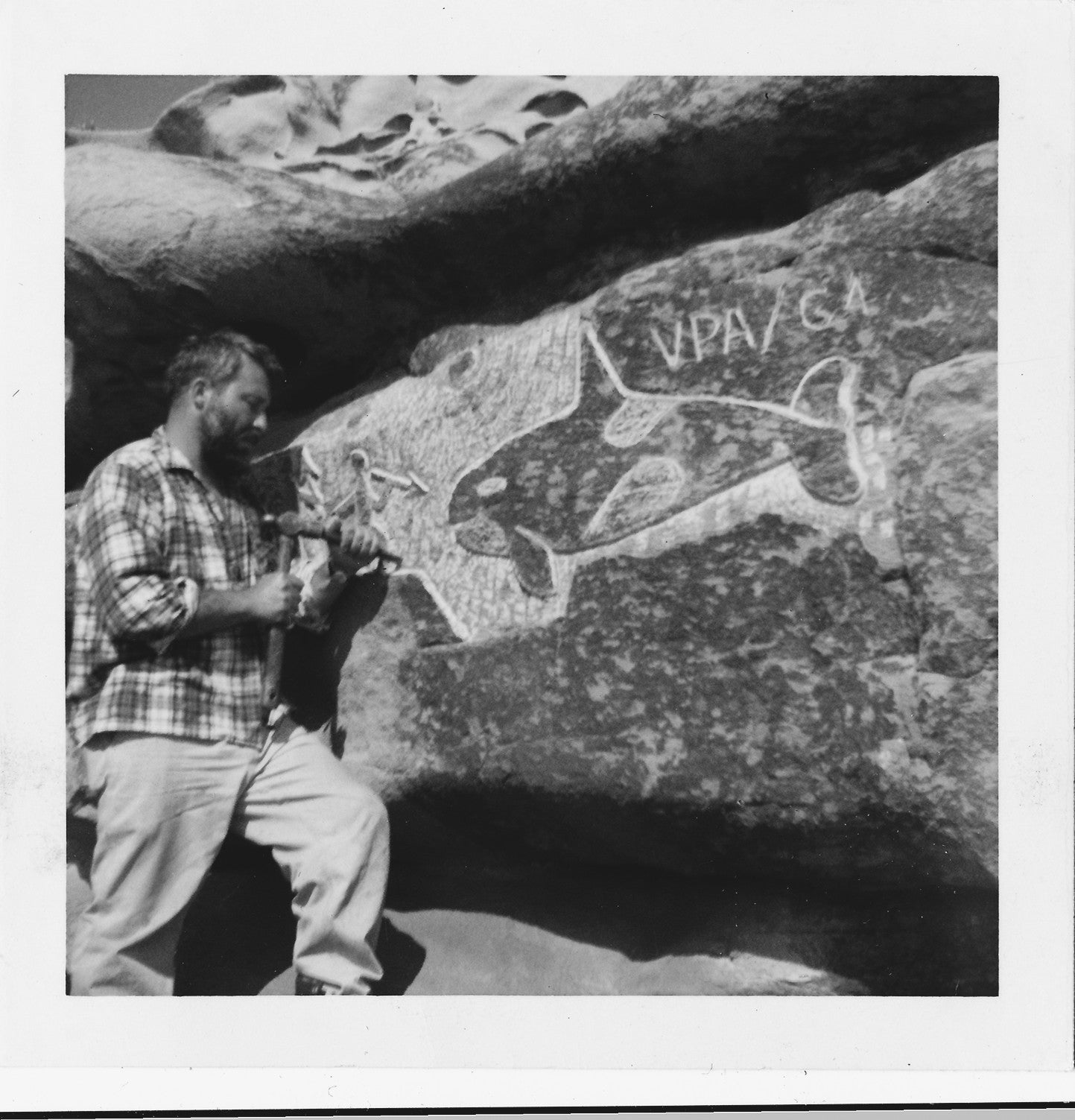

Killer whales had always been seen as bloodthirsty sea monsters. That all changed when a young killer whale was captured off the west coast of North America and displayed to the public in 1964. Moby Doll—as the whale became known—was an instant celebrity, drawing twenty thousand visitors on the one and only day he was exhibited. He died within a few months, but his famous gentleness sparked a worldwide crusade that transformed how people understood and appreciated orcas. Because of Moby Doll, we stopped fearing "killers" and grew to love and respect "orcas."

Published in Partnership with the David Suzuki Institute.

Mark Leiren-Young is a journalist, filmmaker and author of numerous books, including Never Shoot a Stampede Queen, for which he won the Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour, and The Green Chain, which is based on his award-winning film of the same name. His article for the Walrus about Moby Doll, the first orca publicly exhibited in captivity, was a finalist for the National Magazine Award, and he won the Jack Webster award for his CBC Idea’s radio documentary Moby Doll: The Whale that Changed the World. Leiren-Young is currently finishing a feature length film documentary on Moby Doll.

“[Leiren-Young] skillfully weaves whaling history and information about the growth of scientific knowledge of the whale life cycle and social behavior into this account ...This well-written book will appeal to general readers interested in the topic.”

—Library Journal

“Outstanding and inspirational. Similar to the award-winning Blackfish, this book could be a game changer.”

—Marc Bekoff, University of Colorado, author of Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence

“Mark Leiren-Young lays out the distressing tale of the capture of wild orca in the 20th century, and how one particular whale, Moby, became a kind of martyr. His book is detailed, edifying and amazing; it speaks to our dysfunctional relationship with the wild.”

—Philip Hoare, author of The Whale and The Sea Inside

"Leiren-Young’s mesmerizing story of Moby Doll chronicles a key turning point in our understanding of orcas and details how we now see this species as the highly intelligent and evolved species that it is. Amazing."

—Scott Renyard, director of Who Killed Miracle

"[The Killer Whale Who Changed the World] is a brilliant piece of work, one of the most engaging and readable works of British Columbia history in years. That Leiren-Young is a master with words is evident on every page."

—Dave Obee, Times Colonist

From Chapter Two: Save the Whale

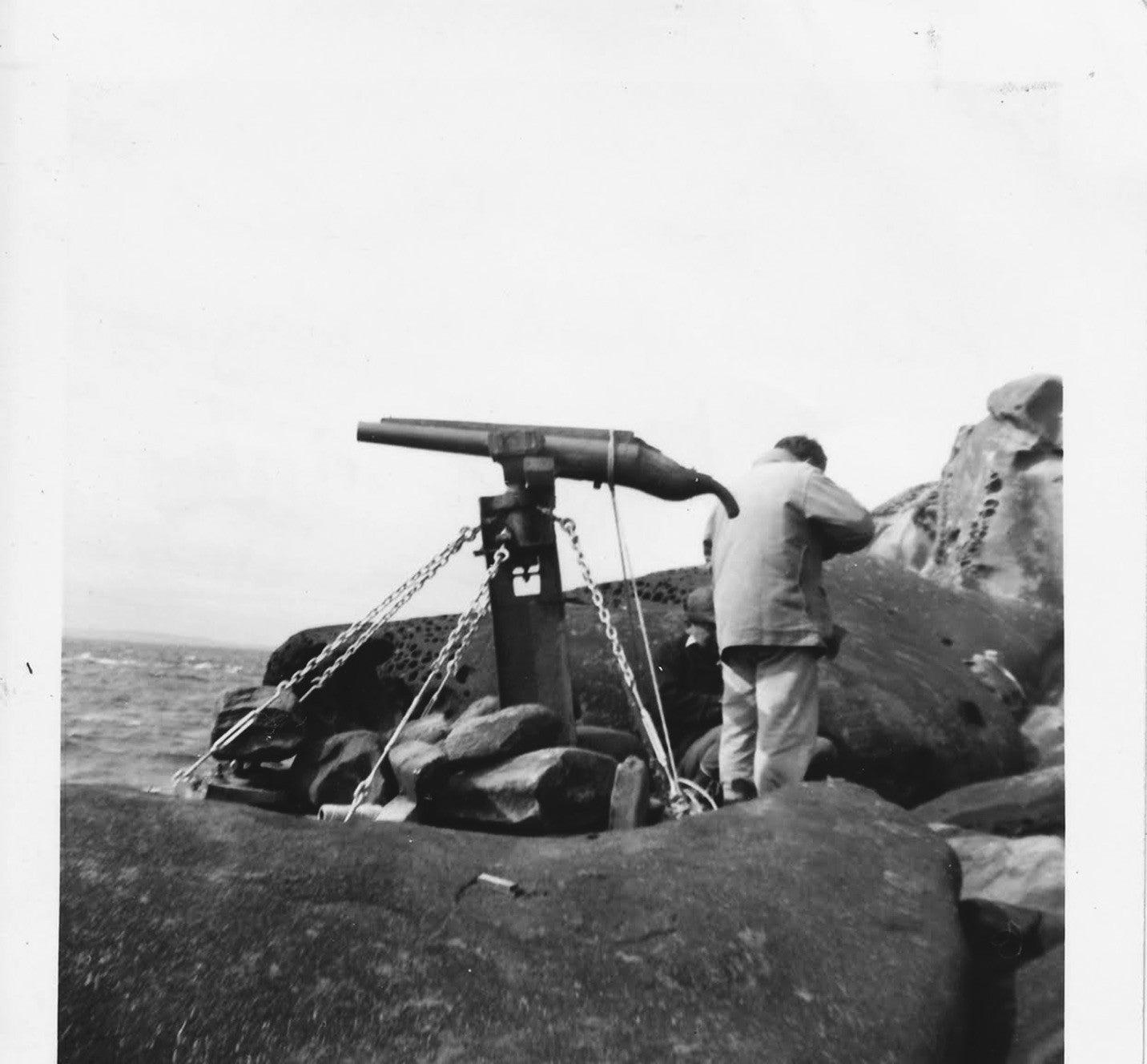

The small killer whale being held aloft in the water off Saturna isn’t breathing, but the two larger whales holding it on the surface, waiting for a puff from their pod-mate’s blowhole, aren’t prepared to surrender. For killer whales, breathing is not an automatic act. If an orca is not conscious, it won’t inhale, and it needs to be on the surface to breathe. A killer can hold its breath underwater for about fifteen minutes—long enough to escape almost any attempt by a human to harass it—but an unconscious whale won’t live long. And if this whale regains its senses underwater and gasps for air, it may choke and drown before it can reach the surface. As shock sets in and consciousness fades, Burich’s victim is drowning. It is about five years old. That means one of the whales attempting to save it is probably its panicked mother or grandmother. The two larger whales consider their injured pod-mate. Is it already dead?

That doesn’t matter.

A mother orca in mourning may hold her dead calf above water for days and transport it for hundreds of miles. The whales off Saturna know their companion isn’t dead. Killer whales can see about as well as humans. Anyone who has watched a killer and thought it was looking back at them from the water, or through the glass walls of an aquarium tank, was probably right. Killer whales see well enough to not just identify other creatures but to identify depictions of other creatures in paintings or photos. They can also recognize themselves in mirrors—a test used by scientists to determine self-awareness and intelligence.

But vision isn’t the most useful sense when you’re diving a hundred meters in murky water. Killer whales listen, using a sense called echolocation, which works like sonar technology. By emitting sound waves and tracking the echoes as they bounce off their targets, these whales can find and “see” anything in the water. As each of these two whales transmits a signal from the front of its head—the melon—they are able to sense the injured whale’s heart pounding, to listen to their baby choke as water seeps into its lungs.

Orcas can hear each other’s calls from more than ten miles away. Their senses are so acute that they can dive to the bottom of a pool to locate and retrieve an object half the size of a wedding ring. There’s a blind Marvel comics hero—Daredevil—whose hearing is enhanced like this, which makes him dangerous enough to defeat armies of ninjas. Orcas basically have the same superpower. They don’t just “see” objects; it’s possible they can echolocate what’s inside of them. There’s anecdotal evidence to suggest they can detect whether a female from our species is pregnant before the expectant mother can. So these whales know that their pod-mate’s organs are still functioning and that they won’t be for much longer. Orcas will work together to support and transport their injured mates for weeks at the risk of their own health.