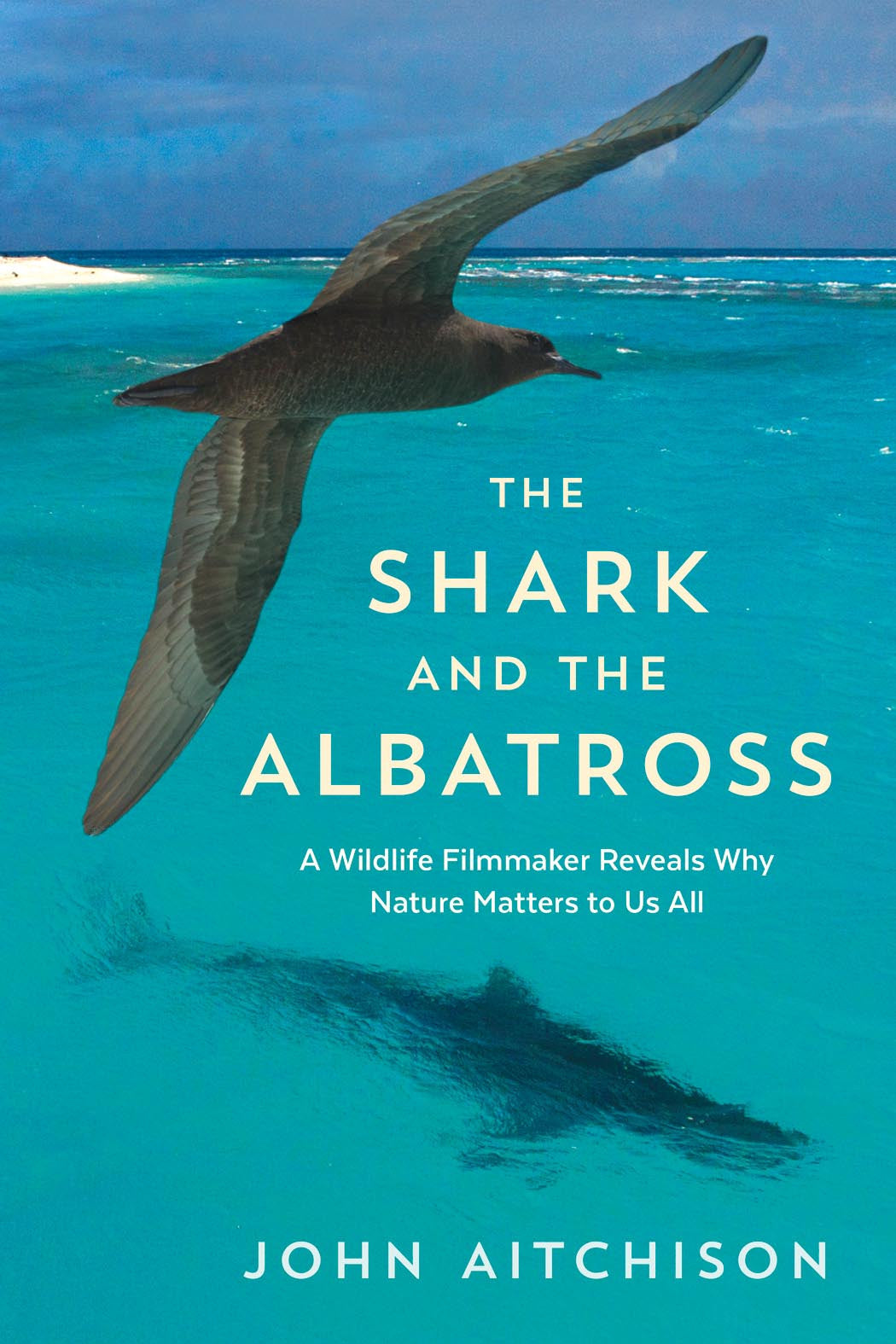

The Shark and the Albatross

A Wildlife Filmmaker Reveals Why Nature Matters to Us All

- ISBN: 9781771642187

- Tags: Carl Safina, John Aitchison, Nature & Environment,

- Dimensions: 6 x 9

- Published On: 05/06/2016

- 272 Pages

- ISBN: 9781771642194

- Tags: Carl Safina, John Aitchison, Nature & Environment,

“A must for all those who enjoy insights into the natural world.” –Alexander McCall Smith

The daring and thoughtfully-rendered adventures of a filmmaker who travels to the ends of the earth to document animal lives.

For twenty years John Aitchison has been traveling the world to film wildlife for a variety of international TV shows, taking him to far-away places on every continent. The Shark and the Albatross tells the story of these journeys of discovery, and Aitchison’s encounters with animals in faraway and sometimes dangerous places. His destinations range from the remotest parts of Alaska and the Antarctic to India and China. Everywhere he goes, he describes—and photographs, in stunning colour—the triumphs and disasters in the lives of such animals, such as polar bears and penguins, seals and whales, sharks and birds, and wolves and lynxes, including their struggle to survive in a perilous world. And, as the author shows in several incidents that combine nail-biting tension with hair-raising hilarity, disaster can strike for filmmakers too.

John Aitchison is a wildlife filmmaker who has worked with National Geographic, PBS, the Discovery Channel, and the BBC on series including Frozen Planet, Life, Big Cat Diary, Springwatch, and Yellowstone. His many awards include a joint Primetime Creative Emmy and a joint BAFTA, both for the cinematography of Frozen Planet.

Carl Safina is the author of seven books, founding president of the not-for-profit Safina Center, and a winner of the Orion Award and a MacArthur Prize, among others. His most recent book is Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel

."This book is in many ways a love song to the places (Aitchison) has spent time in and the animals he has observed ...He's is aware of the carbon footprint his work engenders and hopes his films do more good than harm, moving people to "choose to be on nature's side". In the end he simply loves his craft, and his enthusiasm sings off the page." -The Independent

"Through words and photos, Aitchison transports readers to far-flung corners of the earth and displays, vividly, why we should care about our natural world." -Paul Nicklen

"A thoughtful and moving book about wildlife and wild places from someone who’s spent decades observing both behind the lens." -Dr. Edwin Scholes, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

"Most of us will not have the opportunity to visit many of these isolated locales or to see Adélie penguins, leopard seals or polar bears in their natural habitats, but John’s wonderful book provides the next best thing. "

-Joseph T. Eastman, Professor Emeritus of Anatomy, Ohio University

"John Aitchison’s considerable talents as a wildlife filmmaker may only be surpassed by his amazing ability to observe nature and write about it." -Tim Laman, National Geographic photographer

"Aitchison's great hope is that the rest of us, looking at his images, reading his tales, will love these animals as he does. That we will be moved. I was. You will be." -Virginia Morell, Author of Animal Wise: How We Know Animals Think and Feel

"His prose is clear and poetic as he describes running with wolf packs in Yellowstone National Park, witnessing a whale feeding frenzy in Alaska's northern sea, and encountering endangered tigers in India's dense forests, among other adventures around the globe." -Publishers Weekly

From Chapter 3: Peregrines Among the Skyscrapers

Other reintroductions have been less controversial than the wolves’. New York City is not an obvious place to film wildlife, yet it’s home to one of the world’s most exciting birds: the peregrine falcon. This bird of prey has come back from the brink. In the twentieth century peregrines were all but wiped out in America. The story of their recovery shows that, given a helping hand, some wild animals can adapt well to the modern world.

A policeman spills his coffee, sets his car’s wheels spinning and zooms away, with blue and red lights flashing.

‘We got a deer dying on the approach way, we got a cat on the upper roadway, we got falcons on the tower: it’s like being back in the country,’ says the manager. ‘Welcome to the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.’

The bridge was built during the 1960s: a time of confident expansion in the United States when, alongside ambitious engineering projects like building the Apollo moon rockets, the country’s chemical industry was in full flow, producing a miracle pesticide called DDT. Seeds were soaked in it before being sown and tractors sprayed it onto orchards and fields. Crop yields soared as a result.

When the bridge was built across the Hudson River, at the Verrazano Narrows, it had the world’s longest span, suspended from cables almost a metre thick, running from towers more than 200 metres (about 700ft) tall. The peregrines are nesting on top of one of these towers so filming them will be complicated. Without Chris Nadareski it would be impossible. Chris works for the city’s Department of Environmental Protection and every year he visits all the accessible peregrine eyries in New York City, to fit numbered and coloured bands (known as rings in Europe) to the legs of their chicks.

We each put on a harness and a hard hat and are driven in a slow convoy across the bridge to the base of one of the towers. It soars above us like a huge staple. The traffic lane is closed while we unload our gear and take turns to duck through a door small enough to challenge some of today’s larger engineers. Inside there are hot, cramped metal cells, studded with bolts on every surface. The sound is extraordinary: a bass rumble of traffic on the bridge’s twin six-lane highways, stacked one above the other. Sometimes there are loud and inexplicable booms, as if we were deep in the guts of an iron beast. There are very few lights. The elevator is just large enough for three of us. It feels like squeezing into a suitcase. The controls have notes beside them, handwritten in correcting fluid: TOP next to one button and Don’t press, don’t press! by the one above it. Clanking upwards, we all look through a hole in the ceiling, watching the cable winding into and out of the darkness. To reach the uppermost level we climb through circular holes cut in the steel decking, hauling our gear after us with ropes.

When Chris opens the hatch onto the roof there is a welcome flood of fresh air and immediately we can hear the peregrines’ alarm calls. He climbs out and I set up to film. We must all leave once the last chick is banded, so there is not much time. The top of the tower is a smooth metal surface, enclosed by a low rail. The bridge below has shrunk to the width of a pencil and its trucks are the size of rice grains. A container ship passes easily beneath the span. I don’t mind the height but I am worried about the consequences of dropping anything over the side, so I tuck everything loose into my bag before concentrating on the job in hand, which is to film the peregrines as they hurtle past.

They circle, superbly indifferent to the gulf of air below them, taking turns to dive at Chris’s head. He approaches their nest, which is in a wooden box, roofed with plywood and floored with pea gravel. Chris put the box here to encourage the birds to move home because their old eyrie, under the bridge, was in the way of maintenance work. They adopted the new one the next spring. I can see him deftly checking the four young falcons and fitting their bands. The bridge maintenance crew crouch, holding brooms over their shoulders to protect the backs of their heads. Chris takes the chance to show them what he is doing. Part of his skill is in explaining why it matters to balance the birds’ needs with theirs. After all, 190,000 vehicles cross this bridge every day and it was no small ask to interrupt the traffic so we could come up here. By placing the peregrines’ nest box where the birds will have the least effect on the workings of the bridge, Chris is giving something back on their behalf.

On the way down, the guy in the lift says he grew up on Staten Island, where he could see the bridge being built from his house. On its opening day his parents drove him here, intending to cross, but the sign above the toll-booths brought them to a screeching halt. Fifty cents! They drove straight home. That was in 1964.

In the preceding four years, not one pair of peregrines had bred anywhere on the eastern seaboard of the USA.