Where Do Camels Belong?

Why Invasive Species Aren't All Bad

- ISBN: 9781771640961

- Tags: Dr. Ken Thompson, Nature & Environment,

- Dimensions: 5.5 x 8.5

- Published On: 8/15/2014

- 272 Pages

- ISBN: 9781771640978

- Tags: Dr. Ken Thompson, Nature & Environment,

- Published On: 13/09/2014

- 272 Pages

Where do camels belong? You may be surprised to learn that they evolved and lived for tens of millions of years in North America—and also that the leek, national symbol of Wales, was a Roman import to Britain, as were chickens, rabbits and pheasants. These classic examples highlight the issues of “native” and “invasive” species. We have all heard the horror stories of invasives. But do we need to fear invaders?

In this controversial book, Ken Thompson asks: Why do very few introduced species succeed, why do so few of them go on to cause trouble, and what is the real cost of invasions? He discusses, too, whether fear of invasive species could be getting in the way of conserving biodiversity and responding to climate change.

Dr. Ken Thompson was for many years a lecturer in the Department of Animal and Plant Sciences at the University of Sheffield. He now writes and lectures on gardening and ecology. He has written five other books, including Do We Need Pandas? The Uncomfortable Truth about Biodiversity.

"This is a well put together book about the science and the philosophy surrounding invasive species."

-the Times

“Thompson makes his case in a lively, readable style, spiced with a healthy dose of sarcasm towards ‘aliens = bad’ fundamentalists. Better yet, he bolsters his argument with plenty of citations from the scientific literature, which adds welcome heft.”

-New Scientist

“Ken Thompson presents a stimulating challenge to our perceptions of nature.”

-George Monbiot

“I raced through this engaging book and found, at the end, that my view of the introduced starlings and dandelions in my backyard, not to mention the countless non-native species in the surrounding country, had shifted into a more optimistic space.”

-Alan de Queiroz, evolutionary biologist and author of The Monkey's Voyage

“The information he presents is compelling . . . This title brings an important minority opinion to light.”

-Library Journal

"Jack Christie is a Tourism B.C. Media Award winner and . . . is especially passionate about British Columbia, so it's no surprise a wonderful guide to the wilderness area of Whistler comes from his experienced hand."

-Bookwatch

From the Introduction

Where do camels belong? Ask the question and you may instinctively think of the Middle East, picturing a one-humped dromedary, some sand and perhaps a pyramid or two in the background. Or if you know your camels and imagined a two-humped Bactrian, you might plump for India and central Asia. But things aren’t quite so simple if we’re talking about the entire camel family.

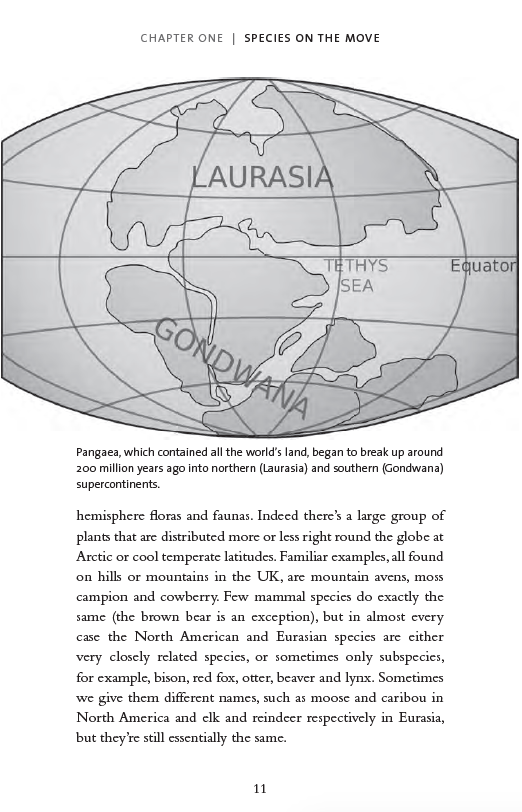

Camelids (the camel family) evolved in North America about 40 million years ago. Titanotylopus, the largest camel that has ever lived, stood 3.5 m high at the shoulder and ranged through Texas, Kansas, Nebraska and Arizona for around 10 million years.Other species evolved very long necks and probably browsed on trees and tall shrubs, rather as giraffes do today. Much, much later camels spread to South America, and to Asia via the Bering Strait, which has been dry land at various times during the recent Pleistocene glaciations. Camels continued to inhabit North America until very recently, the last ones going extinct only about 8,000 years ago. Their modern Asian descendants are the dromedary of north Africa and south-west Asia and the Bactrian camel of central Asia. Their South American descendants are the closely related llamas, alpacas, guanacos and vicuñas (llamas are only camels without humps; all you need to do is look one in the eye for this to be pretty obvious).

Now you know all that, let me ask you again: where do camels belong? Is it:

(a) in the first place you think of when you hear the word ‘camel’, i.e. the Middle East.

(b) in North America, where they first evolved, lived for tens of millions of years, achieved their greatest diversity, and where they became extinct only recently.

(c) in South America, where they retain their greatest diversity.

Or, just to muddy the waters a bit more, is it:

(d) in Australia, where the world’s only truly wild (as opposed to domesticated) dromedaries now occur.

Finally, if you felt able to give a confident answer, can you explain why?

If you think camels belong where they evolved, the question has only one answer: North America. If it means where they have been present for the longest time, the answer is the same. If it means where camels have been present during recent millennia, then the answer is Asia and South America. If camels belong wherever they can thrive without human assistance, then it must also include Australia. These are all perfectly reasonable interpretations of belonging.

And there is nothing particularly special about camels. Dispersal over huge distances is not at all unusual among land animals, and it is almost routine among birds. Horses are much the same as camels, and frogs, toads, shrews, deer, cats, weasels, otters, hares, skinks, chameleons and geckos are among the many other groups that now occur almost everywhere, and do so as a result of relatively recent dispersal – without human assistance – often starting out in Africa or south-east Asia. None of these species have an obvious answer to the question about where they belong – whether they are natives or aliens – any more than camels. Indeed, once you adopt a view of the world that doesn’t assume that there’s something very special about where things happen to be right now (or in relatively recent history), asking where anything belongs tends not to have an obvious answer.