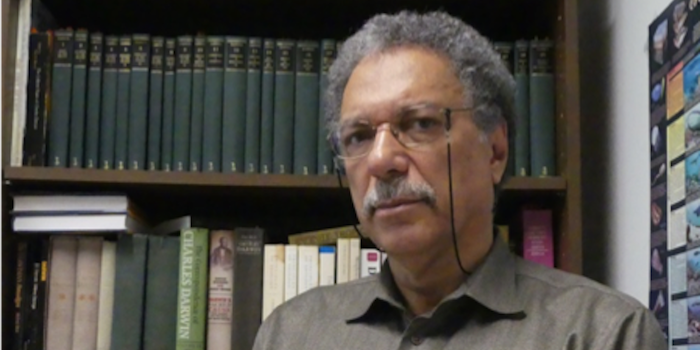

A Q&A with Dr. Daniel Pauly, fisheries scientist, UBC professor, and author of Vanishing Fish: Shifting Baselines and the Future of Global Fisheries (Available Now)

1. Vanishing Fish is a collection of your essays penned over the years. What inspired you to compile them into a book now?

There are several reasons why I compiled these essays into a book. One was the opportunity provided by a 4-month mini-sabbatical at New York University; another is that some of these essays, especially the one on ‘Shifting Baselines’ have become influential but are not seen as part of a whole. The whole is the vision of fisheries that I have developed over decades of work.

2. What was it like to see the term shifting baselines enter the popular lexicon 20 years after you coined it?

The essay on ‘Shifting Baselines’ was written at the request of the Editor of Trends in Ecology and Evolution, who needed a one-page filler for a 1995 issue in order to be able to go to press. I wrote it right away, never thinking that it would have the impact that it did have. But this is common in science: authors cannot predict which of their ideas will fly, and which won’t take off. I was lucky that colleagues noticed this essay and tested whether its claim applied.

3. Do you see any connections between your research and the global social justice movement? If so, what are they?

My research was from the onset (in the 1970s) strongly influenced by the cultural and social transformation sweeping through the Western world in the 1960s. Because I am biracial, I could see more clearly than some people that the newly independent, now called ‘developing’, countries were getting a lousy deal in sharing the wealth of the world. Thus, as did many young people in the 1960s, I launched myself into something that I thought would improve the world; I guess I got stuck into that groove.

4. To what extent are the problems of Canadian fishing stock a representation of the rest of the world’s fishing crisis? What are the major differences between the current situation in Canada and the rest of the world?

When I was a student in Germany, Canadian fisheries research was considered the best in the world, on par with its hockey prowess. Then came the collapse of Northern cod, and Canadian fisheries science stood naked: the assessment of cod was marred by elementary mistakes, magnified by the monster computers then in use, and driven by politicians entirely captured by the fishing industry.

One result of Canadian fisheries policy is that our country has turned from a traditional exporter of fish to a net importer. Our neighbor to the south (still) has a fisheries management system that is much better. Notably, stocks that have been overfished have to be rebuilt to acceptable levels within 10 years. In Canada, everything, including the state of the stocks, is subject to “ministerial discretion”. Such discretion is what drives fish stocks into ditches.

5. How do indigenous rights, and increased sovereignty over their ocean territories, contribute to the potential solution to overfishing in Canada and, for that matter, other countries?

Indigenous participation in fisheries – whether subsistence or commercial – is a tricky issue. Transparency is important here and I was amazed when I discovered that the Inuit catches along our Arctic coastlines are neither compiled nor included in the catch data that Canada reports annually to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO). I wonder how you can manage fisheries that you treat as if they did not exist?

6. For coastal communities or people involved in the fishing industry, the importance of healthy fishing stocks is clear. Why should the general public pay attention to this (plankton stew, you mention)?

I have no illusion about the general public being interested in serious fisheries issues. In fact, we expect too much from regular folks who, after a day of often dreary work, are supposed to be interested in climate change, plastic in the sea and disappearing rhinos.

What we need rather, is for our politicians to understand that they cannot continue to promise a liveable world if nothing is done to keep it going. It is the role of environmental NGOs to remind them of this, and to provide solutions worth fighting for to those members of the public who can and want to be involved.

7. In a 2003 NYT article, you mention that you and your team created a mandate “to look at the whole world.” When did you realize this should be the focus of your work?

There are in Canada 4 levels of government: First Nation, Municipal, Provincial and Federal. Similarly, there are international institutions working at regional (the OAS, the EU) or global levels (the UN, the FAO, the WTO, etc.). There is a need for research appropriate to each of these levels. Thus, evaluating the effect of a salmon run in river in B.C. on the economy of a First Nation group is appropriate, but this is not going to help the Canadian delegate to the WTO regarding governments’ subsidies to distant-water fleets.

Similarly, while the Department of Fisheries and Oceans must review and propose quotas for all managed stocks in Canada, this doesn’t help the Canadian fish importer who would like to ensure that the fish they sell was not caught by an enslaved crew. Yet, despite the clear need for an international dimension to fisheries research, virtually none get funded by the Canadian government (same in other countries). Thus, Sea Around Us is funded exclusively by US and European philanthropic foundations that appear to understand the interconnectedness of the world better than the folks in Canada and other countries who allocate government funds for research.

I must admit, additionally, that working on the global oceans, with all fisheries of the world is my way of continuing to work on and for developing countries. There are enough colleagues who work on their own, wealthier countries.

Want to know more? In Vanishing Fish, renowned marine biologist Dr. Daniel Pauly provides a fascinating analysis of our collapsed global fisheriesm, and a revolutionary vision for their future.